TraMod TALKS with Spanish Architect Angel Borrego Cubero

Javad Eiraji Exclusive Talk with Madrid-Based Architect Angel Borrego Cubero: Tradition + Modernity in Architecture

Angel Borrego Cubero (1967, Spain) A Madrid-based architect and head of the Office for Strategic Spaces (OSS), Angel Borrego Cubero has received accolades for his contributions to architecture and urban research including the INMOMAT Real Estate Award 2023 and the COAM Award 2015 with Special Mention, both from Madrid Architects Association. He also won the NAN Architecture and Construction Award for Best Rehabilitation Project in 2016 and was part of the Golden Lion-winning Spanish Pavilion at the XV Biennale di Venezia in 2016. He was a nominee twice at the EU Mies van der Rohe Awards. In the realm of documentary filmmaking, his feature 'The Competition' earned him the First Prize of the COAM Award 2014 of Madrid Architects Association and the Architecture Dissemination Award of the XIII Spanish Biennial of Architecture in 2016. In 2023, Borrego Cubero was selected by the Venice Biennale to create a documentary on the 1st College Architettura. Borrego Cubero holds a Ph.D. in Architecture from the School of Architecture ETSAM of UPM Madrid Polytechnic University and an MArch from Princeton University, where he was a Fulbright scholar. With over two decades of teaching experience, he has instructed architectural design at Princeton University, Pratt Institute in New York, the University of Alicante in Spain, Keio University in Tokyo, the Hong Kong Design Institute (HKDI), and the School of Architecture ETSAM since 2001. His pedagogical innovation project, 'La Historia de la Escuela' won the Research Prize of the XIII Spanish Biennial of Architecture in 2016. / www.o-s-s.org

OSS recent project LA CARBONERIA, won the FIRST PLACE in TraMod AWARDS 2023 in professional, architecture, built category

Javad Eiraji: How do you see the contemporary architecture of the world? What do architects/designers pay attention to? Where is its way going to

ABC: Architecture is radically changing from what its professional outlook was only a few decades ago. The imagination of the recent past was built on a certain anxiety of population growth and the lack of natural resources. It seems clear now that it is not resources, but refuse (CO2, contaminants, etc) that became the larger issue. Also, population is peaking globally, many countries will decrease, and growth will be localized, not global. These are polar opposite considerations and architecture thought and practice reflects these changes in outlook. Architecture and its surrounding planning have become more rigid and fearful, and it is required to extract more predictable wealth out of the financial resources available. This trend, though perhaps understandable, sucks some of the necessary air out of youthful innovation. At the same time, we are witnessing a renewed interest in traditional modes of climate adaptation and traditional construction techniques and how to make them relevant to modern systems and processes. It is interesting to think of these shifts as they modify our perceptions of the past and the future and how different traditions are able to adapt to all the different and constantly shifting challenges

Javad Eiraji: What is the meaning of “Tradition” and “Identity” for you? How do these effect architecture

ABC: Identity is fluid and, to some extent, something opaque and difficult to define. Identities run a continuous gamut of scales from the constantly shifting individual to the family, the neighborhood, the city, etc. But it is perhaps arguable that identity rests in the perception of each one of us, it is a mental image that we form of ourselves, of a group we belong to, or even an image we form about others. As architects, some of us try to find and express these identities in our different designs, according to the scale of the client, the material context, the economy, the history, etc. There’s some aspects of these identities that repeat through time and which remain, disappear and adapt according to their appropriateness. Tradition is what works over time. It is interesting that traditions, in this respect, is exactly defined as those uses that have changed enough through time to adapt to the different moments and needs in order to survive as acceptable. It is perhaps in the nature of every tradition to be open to change, or risk utter obsolescence and disappearance. In essence, then, tradition and identity though very difficult to define, they form part of the daily assumptions we make to communicate and work, and are subject to constant discussion and modification. It is clear we live in one of those times where these are being discussed globally with special intensity everywhere, and architecture is reflecting this

Javad Eiraji: How can interaction between past and today or even future happen

ABC: We actively strive to detect which aspects of history, which narratives, can be put to work today. In essence, we try to understand histories, relationships, traditions, etc., as positive tools that add value to each design. So, in our case the interaction between the past and the present or the future is very direct, and we make an effort to make this so, always looking into the details of what can be used from the past and how to make sense of it. There are no defined rules for this since knowledge and context are always in motion, always in transformation, and every project offers new, specific conditions to look into, but practice and dedication always help

Javad Eiraji: Your recent project, LA CARBONERIA, won the FIRST PLACE in TraMod AWARDS 2023, among more than 200 projects from 20 countries. Would you please talk more about this and let us know how interaction between tradition and modernity is going on in this project

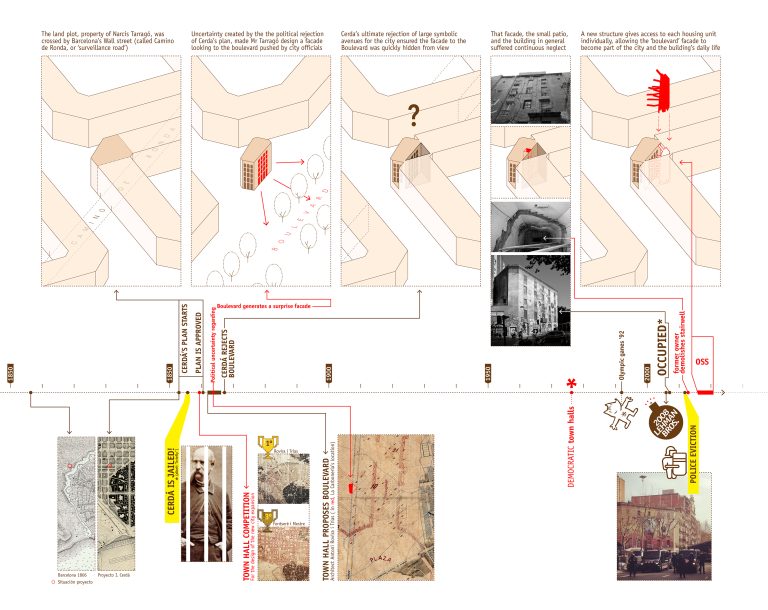

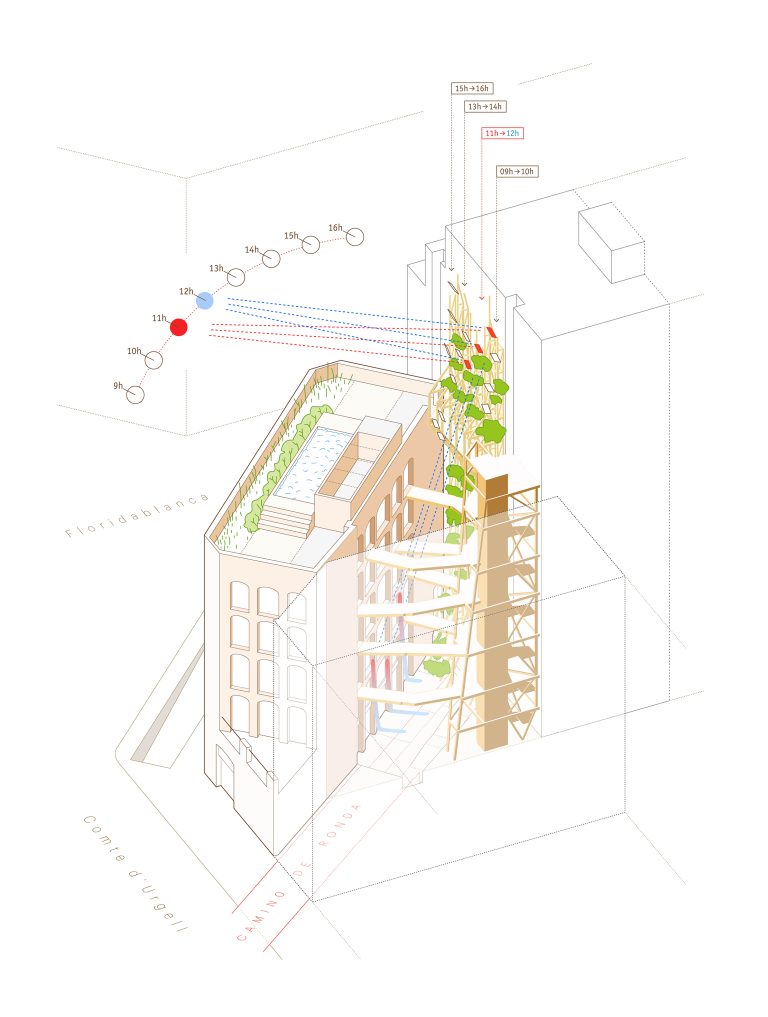

ABC: In the case of La Carbonería, its XIXth century origins and its relationship to the history of Barcelona’s industrial and urban development became the most important aspect of its sustainability strategy. In that respect, we were able to quantify the impact of history in the project. We were also interested in designing a contemporary interpretation of the ‘neighbor’s patio’ (‘patio de vecinos’ in Spanish, which is a very traditional typology for the organization of comunal life), and the dramatic walkways act as an access gallery, but also as private terraces where to do comunal life. We were also adamant about retaining the energy management that the traditional construction methods had provided the building with, so we did not modify its structure or added useless insulation for the climate. New windows, traditional shutters and the substitution of the dilapidated roof allowed us to achieve a very high energy rating for the building. We included some vegetation to help in temperature management during Summer and placed some mirrors strategically for the capture of Winter sunlight for the lower floors in the patio. It is a design that reminds of some aspects of the vegetation and light treatment of Mediterranean and islamic architectural traditions still present in Spain in general and the Mediterranean coast in particular

Javad Eiraji: Which aspects of traditions can be used in architecture

ABC: This is a difficult question, since it seems to me it must necessarily be open to the different approaches of the different professionals and practitioners. It is always a balancing act between the expectations and needs of society on the one side and the artistic desires and the professional experiences and thought or intuitions on the other. All these must be worked out in a somewhat happy solution or result in order to be acceptable, accepted or realized. In our case we are interested in historical details or certain traditions that suddenly become alive and organize a design around them. We are interested when these elements become the center of attention and they help organize a vision for the future. It can be the reuse and interpretation of traditional building systems, or ways to organize and negotiate the relationship between the individual and society… but in our practice these issues become the center of a certain design, and not just resources we can label to comply with expectations

Which factors (forms, meaning, function or user) must be studied in combination of tradition and modernity in architecture

ABC: Again, this is a difficult question, with the answer necessarily varied and changing over time. Both tradition and modernity, if we understand them in an open way, will include all aspects of any discipline, and perhaps even more so of architecture.Tradition and modernity can coexist and enrich each other in architecture. This kind of approach allows for a thoughtful and context-sensitive approach to designing buildings that reflect both historical continuity and contemporary innovation. It’s about adapting what is there already and integrating what you add with what you find In contemporary architectural forms, we seek innovation and often a departure from historical precedents based on modern materials and technologies, but very often we revisit traditional forms: Vaults and arches are back, ornaments on facades can be seen again yet 3D printed, the mix of uses of the traditional public space is periodically studied and adapted… Symbolically, buildings reflect the values and beliefs of a particular community or time period. Nowadays, our ever growing environmental consciousness pushes us to go back to traditional materials, techniques and solutions that were forgotten for a while: rammed earth, ceramic tiling, cross ventilation, greenery, shades, patios, galleries etc. Modern architecture is looking for sustainability that includes energy savings, low environmental impact, adaptability, durability, local sourcing… But many of these goals were already inscribed in the traditional design practices and processes before being SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals). We are now trying to rely on locally sourced materials and craft in order to reduce embodied carbon emissions. There is a strong belief that wood can solve many of our sustainability issues in the building industry (in my opinion this interest is now being strongly pushed by hard industry and deserves a more balanced and careful evaluation). And, we are rediscovering the virtues of clay, either with rammed earth, bricks or ceramic. Traditional materials and processes can coexist with more innovative ones. Modern architecture is probably more concerned than traditional architecture ever was with user comfort, accessibility, inclusivity, privacy etc. , much of which is codified into laws, regulations, and the desires of the client and society at large. The challenge is perhaps to interpret or balance these intelligently